Grief is not just about dying in the physical form. It can be a change in relationship status, losing or retiring from a job, imprisonment, a diagnosis of a learning disability, or even a long-term mental or physical illness.

Grief is personal. There are no rules or stipulations to be adhered to. It can wax and wane, like the moon, and leave you feeling drained of emotion.

For the majority, grief does not flow in a smooth, linear fashion. There are peaks and troughs, chasms to navigate and mountains to climb before some semblance of normality ensues. Even then, it may be a ‘new’ normal to contend with.

A personal journey

My mother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in February 2008. I remember sitting in the hospital waiting room with a bunch of rainbow balloons. She loved balloons and always said they lifted her spirit. As she walked towards me I knew, in the pit of my stomach, that it was not going to be good news. I will always remember her smile and inner strength as she put her arm in mine and we walked, in silence, to the car.

The next few months were a blur. The cancer was too far gone to warrant chemotherapy and she only managed one session before, reluctantly, admitting defeat. I was blessed to have a wonderful relationship with my mum. My father had died when I was two years old and even though she re-married a year or so later, mum imparted enough love for them both. She was my world and the thought of losing her was devastating.

Five Stages of Grief

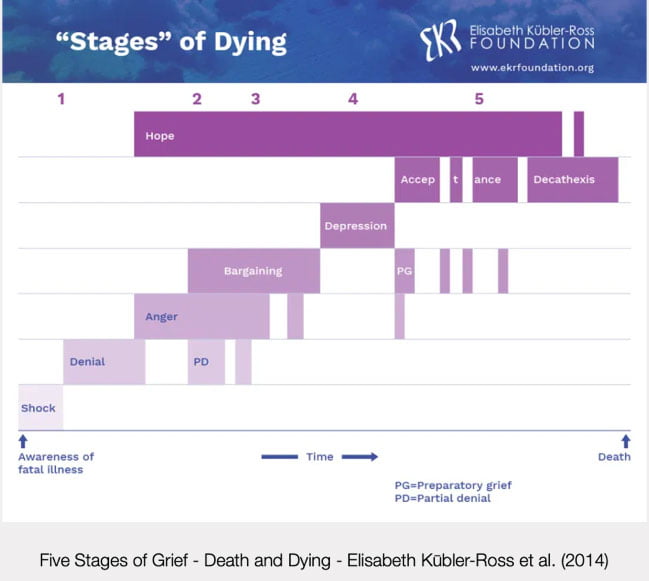

Swiss-American Psychiatrist Elisabeth Kūbler-Ross pioneered understanding of grief, and the process felt by those left behind after the death of a loved one. This was an aside, however, as Kūbler-Ross had initially devised the Five Stages of Grief model (FSoG) to help describe the process patients with a terminal illness go through as they come to terms with their own death.

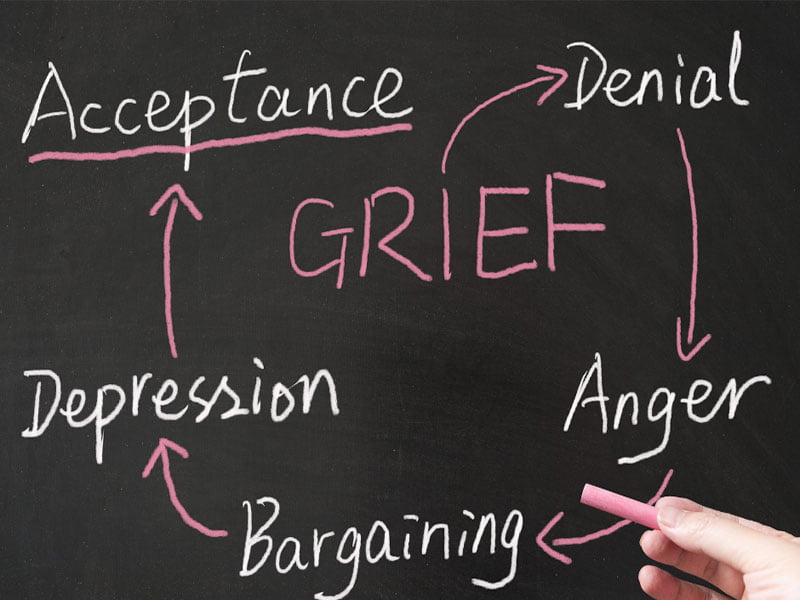

Kūbler-Ross determined that the FSoG model consisted of:

- Denial – Is there an incorrect diagnosis?

- Anger – Why me, it’s not fair!

- Bargaining – Negotiate for life extension, changing habits etc.

- Depression – What’s the point? Why bother with anything, I’m going to die anyway.

- Acceptance – It’s okay, preparing for the grief of loved ones.

Upon reflection this model makes sense in many ways. At the time of grief, it is difficult to ascertain the exact feelings and emotions which are all-consuming and engulfing.

I remember, vividly, a moment when I asked my mum if she would like to sit in the conservatory and look at the garden rather than the confines of her bedroom. She responded quickly and without emotion: “What’s the point?” This tethers perfectly to the fourth stage of FSoG. I was not aware of it at the time, but many years later it makes so much sense.

As the weeks moved on mum seemed to become more settled and her mood lifted. We would sit and look through photo albums and she would name all of the long-deceased relatives in the fuzzy black and white photos. She was at the final stage – acceptance.

Personally, it was a period of calm and chaos. I did not realise it at the time, but I was going through my own interpretation of the FSoG. Late at night I would speak to the darkness, extolling my anger whilst bargaining some of my life years for hers. I would mask my sadness and depression from my family and when spending time with mum I became the ‘court jester’, with the sole purpose of attempting to lift her spirits.

On the 27th of April, 2008 mum began her journey on the Liverpool Care Pathway, one day before my daughter’s sixteenth birthday. Seven days later she was gone, and my world imploded.

Words mean everything and nothing

There was a deluge of copious well wishes and words, imparted from the lips of others, that made me want to curl up in a ball and never face the world again:

“Time is a great healer.”

“It was her time to go!”

“She’s in a better place now.”

They meant well. They are said with good and heartfelt intentions, but the anger of losing someone so special was all engulfing.

At the time of her passing I had no idea that I was neurodivergent. I had undiagnosed ADHD with autistic traits. You may ask why that is relevant to this blog, but bear with me.

Thomas E. Brown, Ph.D is a clinical psychologist specialising in ADHD. He explored the correlation of ADHD and intense feelings, and explains why (and how) ADHD sparks such intense anger, frustration, and hurt:

“Challenges with processing emotions start in the brain itself. Sometimes the working memory impairments of ADHD allow a momentary emotion to become too strong, flooding the brain with one intense emotion.”

I was obviously struggling with emotions, but the level of intensity was overwhelming. I had a full-time job, a home to manage, a husband and two children to support, as well as being a part-time university student who had recently had a hysterectomy and throat surgery. I felt as though my world was crashing around me and there was no light at the end of the tunnel.

Anniversaries

My husband has always been my rock. He would hold me when I woke up crying and reassure me that everything would, eventually, be okay. I continued with my routine of work, family and studies. At the beginning of November, I felt a level of grief I had not experienced before. The 15th would have been her 67th birthday, where she would have been fussed over with an abundance of love and gifts from her family.

Christmas arrived soon after, her favourite time of year. She would stand outside the front door at midnight on Christmas Eve. She always said the air smelt like Christmas at that specific time. Her passing made Christmas a struggle to contend with.

There were, of course, our birthdays, anniversaries and milestones with our children, all of which were missing one important element – mum.

Managing grief

On my journey through grief, I have discovered that there is no right or wrong way to grieve. There are no time limits or protocol to follow. Grief is personal and individual to everyone it touches.

The day my mother received her diagnosis I began a journal. I would write about how I was feeling, the impact of what terminal cancer meant and how it would affect us all. Each day I would add a short paragraph or a quote I had read. When I reflect on it now, I was using the FSoG model as an outpouring of grief. It was also a coping strategy to help manage my undiagnosed ADHD symptoms, such as short-term working memory. I would have a multitude of thoughts that would swirl around in my head, not making much sense. Once I had put pen to paper, I felt a sense of relief that what I was feeling was reasonable and plausible.

A month or so passed and my GP referred me for counselling where, after a course of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), I was duly diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Grief is cyclical and messy. I can be driving in a familiar place and a memory of mum will come to the fore. A song will play on the radio that could make me laugh or cry. The smell of her perfume as I walk past someone wearing it. The pain of losing her will never go away, it just gets more manageable.

Talking helps

My mother was a minimalist and family photographs were never prominent in our home. After mum passed, I made sure that there were photographs of her in every room. She was a spiritualist teacher and had a plethora of students who would love to chat about their time with mum and how special she was. I relish those conversations and have found that talking about her keeps her memory alive.

A few years ago, I had her old video camera tapes transferred to digital files. My daughter and I laughed and cried whilst watching them. I always tell my daughter:

“How lucky we were to have such a wonderful person in our lives who left us with so many happy, unforgettable memories.”

Cruse Bereavement Support offers a range of ideas to help manage loss and grief on its website. It has a helpline, which is available seven days a week, as well as online chat support which is completely free of charge.

Never underestimate the power of talking to someone. It can make all the difference in the world and now, thirteen years later, I can stand outside my house on Christmas Eve, look up to the sky, smell the air and smile.

Written by Beverley Nolker, Education Development Officer for Psychiatry-UK and the HLP-U Clinics.

Hi Bev that’s so very well written and yes your mum has a very beautiful soul. I believe myself that the soul lives on forever in some form and in a world we can’t really comprehend just the same as when we’re in the womb it’s the only world we know and learn later that it was the place where we are physically formed and at the time we had no idea that this world existed.. Your mum brought so much Joy to so many people and yes she was very special and helped meto believe in myself especially that she introduced me to a guide during one of her meditations, I think we were at the seekers trust.. I laughed about the name that came to me Lobsang Rampa but then found it he was a tibetan monk and had many followers. There is an amazing story about him who many think isa hoax but I know different because no one told me about him. He came to me during that meditation. Your mum did so many wonderful things while on this Earth plane and I for one will never forget all the amazing evenings at her home and was an honoured and grateful to be in her presence. Much love to you as always. X

Well done Bev. Beautiful words…xxx